By David Schmidt | May 11, 2022 | Yachting Magazine

Take an inside look at how Garmin turns ideas into tech by Yachting Magazine

Google Maps directs me onto Garmin Way, and I absorb the scale of what I’m seeing. A seven- story tower punctuates an otherwise two-story landscape ahead. Maintained grounds, ornamental trees and curving sidewalks convey a campus atmosphere. Since 1989, Garmin has evolved from two electrical engineers into a publicly traded juggernaut of technology manufacturing.

There’s something odd about the triple-stacked recycle bins. Then, I spot a touchscreen and wheels. As with everything at Garmin’s Olathe, Kansas, headquarters, I’m told that in-house engineers “enhanced” this otherwise off-the-shelf robot by scanning the massive factory floor and loading bespoke cartography into its memory. This, plus the robot’s built-in lidar sensors, lets it deliver materials to its human colleagues, sans collisions.

The art of leveraging technologies to build products is evident everywhere. It extends to the industrial design department, where 3D printers and industrial artists create prototypes; the automated factory floor, where robotic arms hammer out repetitive tasks and free humans to do quality-control work; the automated raw-materials warehouse, where robots handle the heavy lifting; and the research and development labs, where engineers create environmental torture chambers. After all, if Garmin doesn’t find the weak links in the more than 235 million products it has produced in its six factories, its customers will.

All of this started in the mid-1980s, when Gary Burrell, an American electrical engineer, and Min Kao, a Taiwanese American electrical engineer, were working for the King Radio Corp. It was an avionics company here in Olathe. The US government was building the Global Positioning System, and Burrell and Kao saw game-changing potential. King Radio didn’t appreciate their vision, so the two founded ProNav in 1989 before rebranding to Garmin (that’s “Gar” plus “Min”) in 1991.

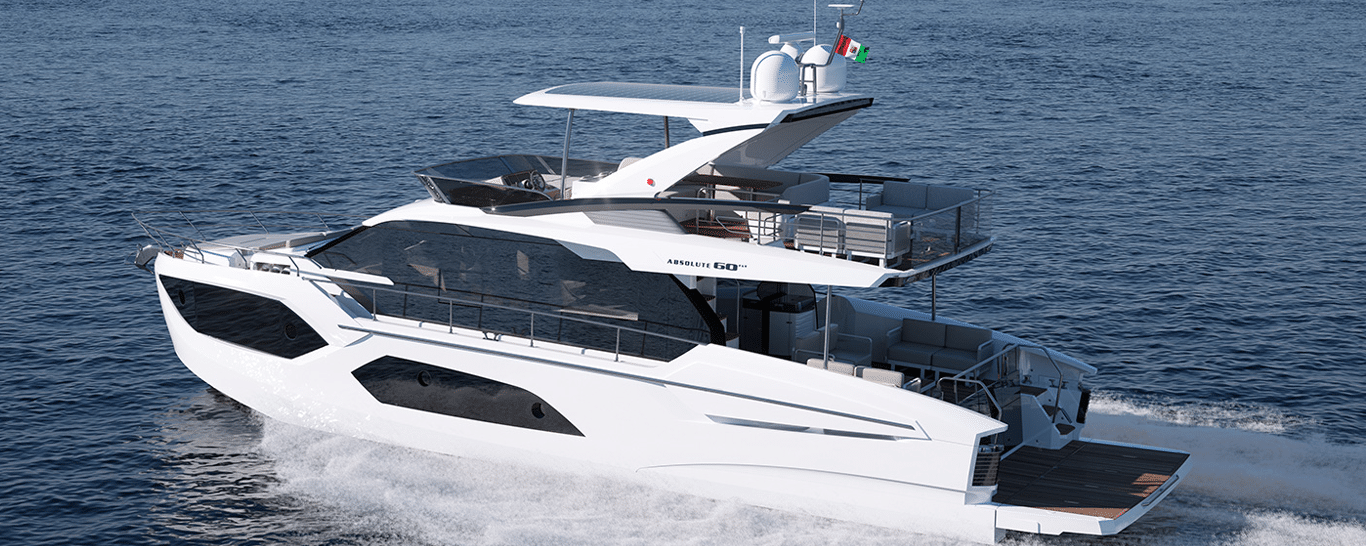

The gamble paid off. In 1990, the company released the GPS 100, the first recreational-level marine GPS receiver. In 1994, Garmin’s GPS 185 was its first combined chart plotter and sonar, soon followed by the first color GPS chart plotter, the GPS220. Garmin simultaneously engaged the aviation, outdoors and fitness markets, plus government-contract work. In 1998, the company began making aftermarket navigation systems for cars.

Garmin went public on December 8, 2000. Business skyrocketed in the mid-2000s when Nuvi navigation systems—with touchscreen interfaces, vector cartography and, eventually, built-in autorouting capabilities—made Garmin a household name.

Despite the advent of smartphones and automotive infotainment systems, Garmin grew annual revenue from a little more than $1 billion in 2005 to more than $4.1 billion in 2020. The business reinvested the boom-year earnings into infrastructure, future technologies and intellectual property, while focusing on how the company could leverage its existing expertise.

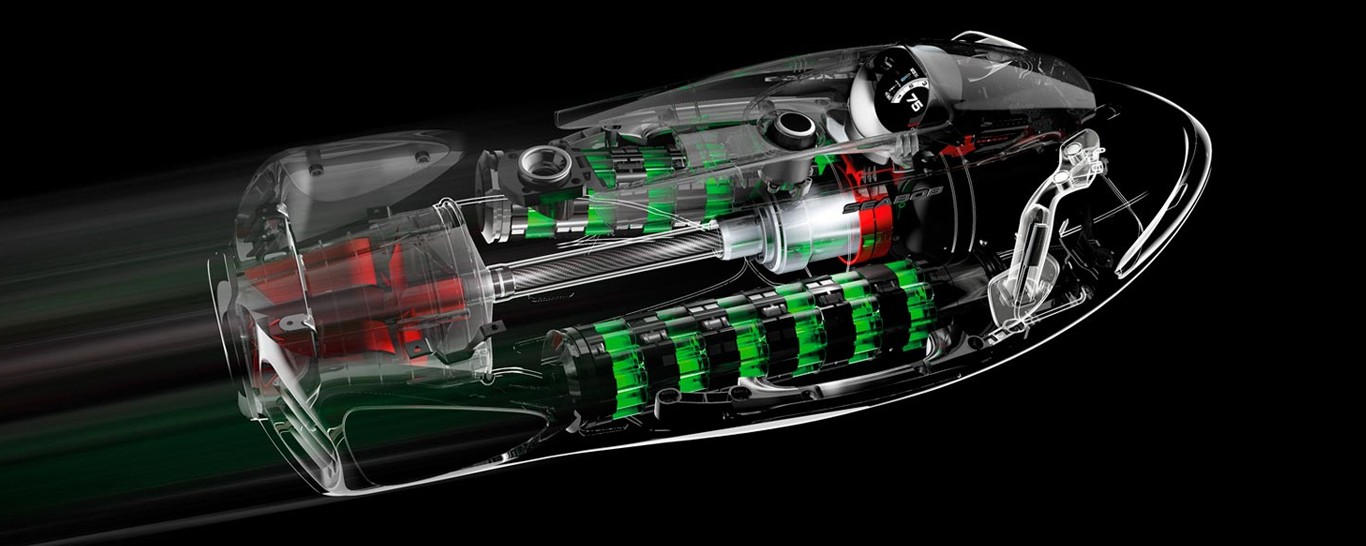

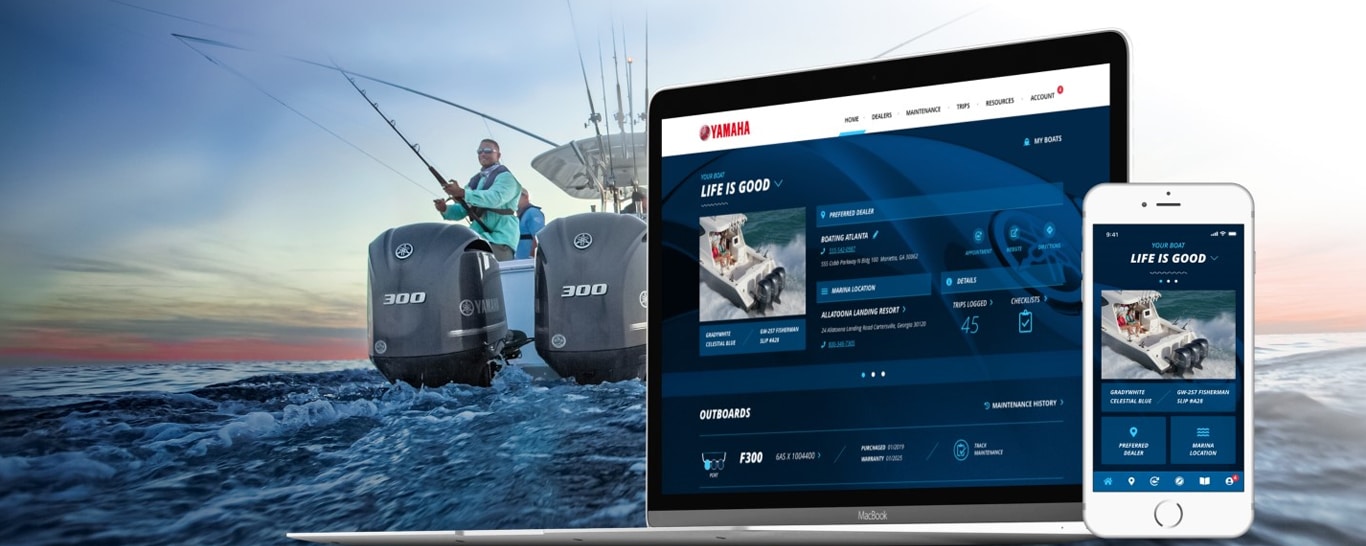

In 2006, Garmin released its first multifunction display—the GPSMap 3000—and by 2007, it incorporated touchscreen displays on the flagship GPSMap 5000. Autopilots arrived in 2008, chirp-enabled fish finders in 2011, all-glass helms and marine-specific wearables in 2013, multibeam sonar in 2015, Doppler-enabled radar in 2016, and in 2018, live scanning sonar.

The company also made key acquisitions—including Fusion Entertainment, Navionics and EmpirBus, and Vesper Marine that extended the reach to onboard entertainment, mobile cartography and digital switching.

“We build our marine equipment in Taiwan,” says Dave Dunn, Garmin’s senior director of marine sales, as we head toward Garmin’s US aviation factory. “But this will give you an idea of what our factories are like.” We pull on carbon-fiber threaded shirts and grounded slippers that prevent static electricity buildup. Then, we enter an air lock. Walls of air nozzles, each angled differently, blast us clean, and we exit onto a seemingly infinite factory floor.

Brian Junkins, Garmin’s team leader of operations and engineering, guides us to the head of the first of six production lines, where machines attach microchips and other components to printed circuit boards, starting with the smallest bits and progressing to the larger hardware. Microchips and components are organized on big reels (imagine old reel-to-reel films but with componentry in place of imagery) that feed the assembly machines. Other machines precisely dispense solder or glue.

Junkins explains that Garmin catalogs each component—“raw materials” in Garmin parlance—with lot, date and manufacturer codes, providing traceability if something fails one of many tests. Garmin employs an interconnected testing process called the “safety stack,” in which certain failed tests stop the production line. These begin with optical inspections of each installed component, some of which are separated by only one-four-thousandth of an inch of silicone.

A staircase leads to the aviation department’s repair section. Toward the back, there’s a warehouse. Raw materials are sorted in stacked plastic bins that stretch several stories high. Humans place orders and robots handle fulfillment, Amazon style.

I meet “Art” and “Jack,” two robotic arms that Garmin engineers playfully nicknamed and enhanced with software to perform repetitive tasks. The arms move fast—and with pinpoint precision. I turn to my left and see three stacked recycling bins before realizing that what I’m looking at is also a robot.

“If we move something on the line, we have to let the [robotics] team know so they can update the maps,” Junkins says.

At the industrial-design group, artists, designers and machinists create full-scale prototypes using 3D printers, CNC machines and their hands. This group, whose backgrounds range from ornament-making to auto-body repair, collaborate with the company’s product engineers to create industrial forms that support Garmin’s functionality.

Brian Sandefur, Garmin’s manager of mechanical engineering, shows me the company’s torture chambers. He walks me through the vibration-and shock-testing rooms, showcasing speaker-type devices that create computer-controlled vibration profiles. Equipment is subjected to hours of testing per axis, up to 40 g of shock. Other rooms allow engineers to conduct similar tests at extreme temperatures (minus 40 degrees to 176 degrees Fahrenheit) or with ultraviolet light. Other machines yield salty fog and prolonged tumbles.

A 2-mile running and walking loop circumnavigates the campus to transit from building to building, and I notice picnic areas and grills. A central courtyard celebrates Garmin’s heritage and future with flora from Taiwan and Kansas. Bike racks punctuate several outdoor spaces. Most employees are wearing Garmin-built smartwatches—not (necessarily) because the people work here but because the watches are the right tools for their lifestyles.

Greg Groener, Garmin’s marine product line manager, shows me around the marine department, where radars, sounders, multifunction displays and other gear are being bench-tested in the hardware laboratory. There’s an electromagnetic compatibility chamber—one of five in Olathe—that engineers use to ensure that Garmin products meet the standards of the Federal Communications Commission. There’s also a software laboratory where features are created and tested, and where real-world problems are replicated and solved.

The final stop is a conference room where I meet Jarrod Seymour, Garmin’s vice president of the marine segment. Seymour has been with Garmin since 1999 and, like many marine-group employees, is an experienced boater. “Garmin’s second product was for marine—we’ve greatly expanded since then,” he jokes, referring to the GPS 100.

While he’s talking about chart plotters, which grew from 8-inch screens in 1994 to today’s 24-inch displays, I realize that the exponential change in size holds true for Garmin itself. The company that began with two forward-thinking engineers now involves 80 international locations and more than 17,000 employees.

A bit later, I ease the rental car back onto Garmin Way and study my mirrors: The construction cranes, robots and skilled workers aren’t visible, but the innovations unfurling behind these walls will be affecting navigation for decades.

Garmin’s headquarters occupies some 93 acres, and the company just announced plans to acquire another 193 acres. My personal Garmin watch counted 10,793 steps (roughly 5.6 miles) during my campus tour. Still unclear of the scale? There’s an in-house Starbucks and a dedicated Garmin-built app for ordering and paying.